I first heard of the club Subterranean A this past January when Darcy James Argue brought his merry band of co-conspirators to Washington DC. It certainly sounded like a hip place. It booked Darcy James Argue for Pete's sake!

Speaking of Pete, I was out for dinner my first day in DC with my uncle Pete and Aunt Julie when I saw an ad for a jazz show at Subterranean A - the JD Allen trio. JD's a perennial favorite of Patrick J up on the fifth floor, suggesting that this Subterranean A place was really plugged into the NPR tastes. I imagined it being some stone-walled room in a warehouse basement, something like Cafe Oto in London, or the Bell House in Brooklyn. A sort of clean, NPR-style DIY venue with lots of folding chairs. But in the end, Subterranean A was much more plugged into NPR than I realized.

Sami Yenigun was temping with WATC during my first 3 weeks on the show. That first Saturday, he told the staff that he was having a concert at his house that night. Sounded cool, but I already had those JD Allen tickets. Then Sami said the concert was of a jazz saxophonist named JD Allen.

So Subterranean A was really just another name for Sami's basement apartment. It suddenly gained a new romanticism. It was close to the chest like a punk rock house party, but with an ethic that put music first, rather than a particular social vibe. How else would you explain JD Allen in June followed by dubstep in July?

Because Sub A was such a cool place, unique in DC, I decided to sit down with Sami and talk about how he got the idea to host shows at his place and how he actually goes about doing it. You can read the full interview at NPR's intern blog In Addition.

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Run From Cover

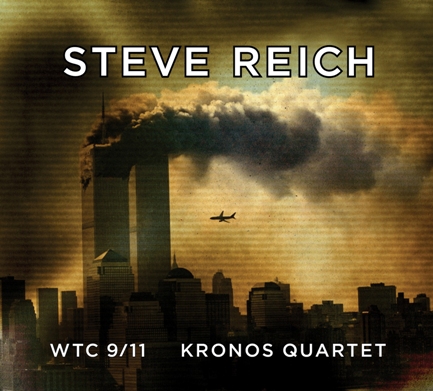

This photo has caused more than a dull uproar since its posting Wednesday afternoon. It's a bit of a surprise considering Steve Reich isn't a name that really inspires anger and shame among contemporary music types. It's been 28 years since an audience member reacted to Reich's "Four Organs" with "Stop. Stop. I confess." He's won a Pulitzer, gets birthday concerts at Carnegie Hall, and has become his own adjective (see reviews of Sufjan Stevens and Darcy James Argue for a taste of "Reichian").

But that didn't stop the torrent of comments, especially from the New York downtown intelligentsia. Composer Phil Kline (whose political music I talked about here) lambasted it as "the first truly despicable album cover I've ever seen." Composer Timo Andres didn't pile on the vitriol, but put together a slap-dash alternative cover. Seth Colter Walls of the Village Voice, Huffington Post, et al has a detailed criticism of the cover on Slate.

It's just all about the cover.

Call it provocative, exploitative, too soon, disrespectful, what have you. It certainly is all those things to different people. That's the nature of an image that has for better or worse been etched into the American psyche.

But just to keep things straight, we are talking about an album cover. Not the music. Granted, Walls heard the New York premiere and his criticisms regard the relationship between a powerful, multifaceted, and nuanced piece and a blunt cover that seems to exploit the terrorist attacks of September 11th for monetary gain, or at least for buzz.

Reich and Nonesuch had to know that this would be the kind of response. Almost 10 years out, 9/11 still seems too soon for reflection or an artistic response beyond mourning. The US is still fighting two wars because of it. And Steve Reich's listeners aren't the Rage Against the Machine types that are used to such visual provocation. I actually feel that Nonesuch execs would likely have preferred something more abstract, or at least something that wasn't as unsubtle as Will Ferrell's dubya impersonations.

In interviews and press releases about the piece, Reich talks a lot about the personal experience of the day - talking to his daughter and son in law for 6 hours, hoping the phone line in their lower Manhattan apartment wouldn't die. He says 9/11 was not a media day for him and his family. They couldn't get back to their lower Manhattan apartment for several weeks. Certainly the image brings those memories flooding back big time. And that's true for just about every American - we all remember where we were when we heard of the attack.

And that's the reason why this image is so problematic, and yet I feel it to be vital to the album's importance. Because of the emotional trauma of that day, we all feel we own a bit of that image. That's why we judge its use in this case, as if we took the photo. I'll admit I was a little taken aback when I first saw the image, doing the whole politically correct "Can they do that?" thing. But then I listened to the piece.

There are a lot of superficial similarities to Reich's class "Different Trains." The same string quartet, the use of prerecorded voices, the exploration of tragedy through the words of eyewitnesses. The piece begins with the pulse of a phone off the hook, joined by a violin, then a second a half step down. The dissonance is grating and makes your hair stand on end. The pulses are joined by the voices of NORAD operators, then police and firefighters on the scene - actual sounds time warped to the present. Like in "Different Trains," these voices become the piece's melodic material, doubled and imitated by the strings. The second movement moves into a more reflective zone, featuring the memories of Reich's friends and neighbors, recounted in 2010. In the third movement, the pulses dissolve into drones, recounting the women who recited psalms over the victims' bodies in tents on the lower east side.

By that point in the piece, I was a wreck, almost sobbing at my computer. Certainly it had a good deal to do with the images that flashed across the back of my closed eyes - the media images, yes, but also the church service I went to that night, the congregation of candles. I was responding to my memories, yes, but when the music is off, I can pull up those images and keep my composure.

For me, the most powerful musical experiences are ones that touch on more than basic emotions. But I also believe that sound itself can only communicate so much and it's the listener that brings the powerful meaning to a musical experience. My Dad says that he wells up when he listens to the last movement of Mozart's Jupiter Symphony, knowing that this bright and perfect fugue was the end of his symphonic output. I love the piece too, but I don't have the same thought or the same emotional reaction. The inherent abstraction of the symphony allows for a wondrous array of interpretations, but also some emotional experiences that are more potent than others.

Reich's use of recorded voices, particularly of the first responders, is a blunt expressive gesture. And while the piece ends up exploring other sides of the event, it still boils down to the attack itself and how that instant changed everything. Because the piece's impact is fueled by the specificity of memory, the album cover should reflect that. John Adams' "On The Transmigration of Souls," for instance, was a requiem, and its solemn skyline reflected that. Reich's "WTC 9/11" is the day and its aftermath boiled down to its emotional essence, almost reporter-like in its presentation. The cover reports the pivotal action of the day.

The emotional directness of the piece and the cover steps close to the line of exploitation in how powerfully it plays with our memory and emotional. But to elicit these emotions is not exploitative in and of itself. It's exploitative when it's used to sell a war or a political campaign. Yeah, a cover is there to sell an album, but Reich has never been one to worry about selling albums (he ran a moving company with Phillip Glass to make ends meet). Instead, appropriating this indelible image for an album cover challenges our emotional and intellectual relationship with the image and with the events of 9/11. Our political correctness monitor responds and we feel that the move is tasteless. But if we recognize that reaction, and give it just a second of reflection, we begin to think about why we feel this way. We think about whether art about a specific event can communicate unaltered truth, or if it's just biased media sensationalism. Our thoughts and memories become more complicated, they keep coming back at different points for days afterward. We're moved to talk about it. Write about it. Argue.

And that brings us here. Just a simple album cover depicting a single event has made us consider what the meaning of art is in the most abstract sense. In the below video, Reich says that the piece will live on or fade away based on its musical merits alone. He's right.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-13318490

In the end, the piece doesn't just bring back memories of September 11, 2001 and store them away once it leaves. The music demands that we examine our emotional reaction to it. We can't just get away with cheap catharsis. "WTC 9/11" is a pandora's box that releases our deepest thoughts about how to deal with history and what art means. A cover that has the power to do the same is the right match.

But that didn't stop the torrent of comments, especially from the New York downtown intelligentsia. Composer Phil Kline (whose political music I talked about here) lambasted it as "the first truly despicable album cover I've ever seen." Composer Timo Andres didn't pile on the vitriol, but put together a slap-dash alternative cover. Seth Colter Walls of the Village Voice, Huffington Post, et al has a detailed criticism of the cover on Slate.

It's just all about the cover.

Call it provocative, exploitative, too soon, disrespectful, what have you. It certainly is all those things to different people. That's the nature of an image that has for better or worse been etched into the American psyche.

But just to keep things straight, we are talking about an album cover. Not the music. Granted, Walls heard the New York premiere and his criticisms regard the relationship between a powerful, multifaceted, and nuanced piece and a blunt cover that seems to exploit the terrorist attacks of September 11th for monetary gain, or at least for buzz.

Reich and Nonesuch had to know that this would be the kind of response. Almost 10 years out, 9/11 still seems too soon for reflection or an artistic response beyond mourning. The US is still fighting two wars because of it. And Steve Reich's listeners aren't the Rage Against the Machine types that are used to such visual provocation. I actually feel that Nonesuch execs would likely have preferred something more abstract, or at least something that wasn't as unsubtle as Will Ferrell's dubya impersonations.

In interviews and press releases about the piece, Reich talks a lot about the personal experience of the day - talking to his daughter and son in law for 6 hours, hoping the phone line in their lower Manhattan apartment wouldn't die. He says 9/11 was not a media day for him and his family. They couldn't get back to their lower Manhattan apartment for several weeks. Certainly the image brings those memories flooding back big time. And that's true for just about every American - we all remember where we were when we heard of the attack.

And that's the reason why this image is so problematic, and yet I feel it to be vital to the album's importance. Because of the emotional trauma of that day, we all feel we own a bit of that image. That's why we judge its use in this case, as if we took the photo. I'll admit I was a little taken aback when I first saw the image, doing the whole politically correct "Can they do that?" thing. But then I listened to the piece.

There are a lot of superficial similarities to Reich's class "Different Trains." The same string quartet, the use of prerecorded voices, the exploration of tragedy through the words of eyewitnesses. The piece begins with the pulse of a phone off the hook, joined by a violin, then a second a half step down. The dissonance is grating and makes your hair stand on end. The pulses are joined by the voices of NORAD operators, then police and firefighters on the scene - actual sounds time warped to the present. Like in "Different Trains," these voices become the piece's melodic material, doubled and imitated by the strings. The second movement moves into a more reflective zone, featuring the memories of Reich's friends and neighbors, recounted in 2010. In the third movement, the pulses dissolve into drones, recounting the women who recited psalms over the victims' bodies in tents on the lower east side.

By that point in the piece, I was a wreck, almost sobbing at my computer. Certainly it had a good deal to do with the images that flashed across the back of my closed eyes - the media images, yes, but also the church service I went to that night, the congregation of candles. I was responding to my memories, yes, but when the music is off, I can pull up those images and keep my composure.

For me, the most powerful musical experiences are ones that touch on more than basic emotions. But I also believe that sound itself can only communicate so much and it's the listener that brings the powerful meaning to a musical experience. My Dad says that he wells up when he listens to the last movement of Mozart's Jupiter Symphony, knowing that this bright and perfect fugue was the end of his symphonic output. I love the piece too, but I don't have the same thought or the same emotional reaction. The inherent abstraction of the symphony allows for a wondrous array of interpretations, but also some emotional experiences that are more potent than others.

Reich's use of recorded voices, particularly of the first responders, is a blunt expressive gesture. And while the piece ends up exploring other sides of the event, it still boils down to the attack itself and how that instant changed everything. Because the piece's impact is fueled by the specificity of memory, the album cover should reflect that. John Adams' "On The Transmigration of Souls," for instance, was a requiem, and its solemn skyline reflected that. Reich's "WTC 9/11" is the day and its aftermath boiled down to its emotional essence, almost reporter-like in its presentation. The cover reports the pivotal action of the day.

The emotional directness of the piece and the cover steps close to the line of exploitation in how powerfully it plays with our memory and emotional. But to elicit these emotions is not exploitative in and of itself. It's exploitative when it's used to sell a war or a political campaign. Yeah, a cover is there to sell an album, but Reich has never been one to worry about selling albums (he ran a moving company with Phillip Glass to make ends meet). Instead, appropriating this indelible image for an album cover challenges our emotional and intellectual relationship with the image and with the events of 9/11. Our political correctness monitor responds and we feel that the move is tasteless. But if we recognize that reaction, and give it just a second of reflection, we begin to think about why we feel this way. We think about whether art about a specific event can communicate unaltered truth, or if it's just biased media sensationalism. Our thoughts and memories become more complicated, they keep coming back at different points for days afterward. We're moved to talk about it. Write about it. Argue.

And that brings us here. Just a simple album cover depicting a single event has made us consider what the meaning of art is in the most abstract sense. In the below video, Reich says that the piece will live on or fade away based on its musical merits alone. He's right.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-13318490

In the end, the piece doesn't just bring back memories of September 11, 2001 and store them away once it leaves. The music demands that we examine our emotional reaction to it. We can't just get away with cheap catharsis. "WTC 9/11" is a pandora's box that releases our deepest thoughts about how to deal with history and what art means. A cover that has the power to do the same is the right match.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)